Hi, I’m Forrest Baumhover

Learn More About Money, Tax planning, and Social Security

I’m a Certified Financial Planner, tax practitioner, retired Navy veteran, and writer. I love to write articles on financial topics that help everyday people learn more about money. I especially like exploring financial planning subjects that no one else has tackled before, writing about IRS tax forms, and helping people with financial questions they haven’t found the answers to.

Tax Planning

Tax planning is fundamental to financial planning. These articles outline how to achieve your financial goals without paying more taxes than you have to.

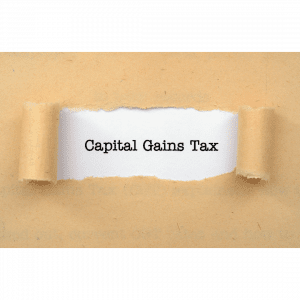

IRS Form 8978 Instructions

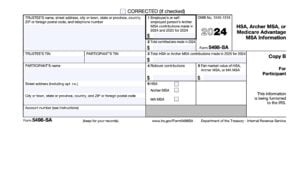

IRS Form 5498-SA Instructions

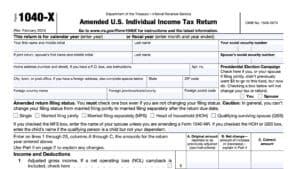

IRS Form 1040-X Instructions

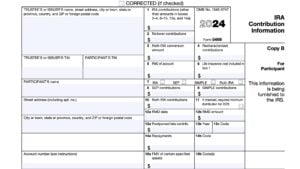

IRS Form 5498 Instructions

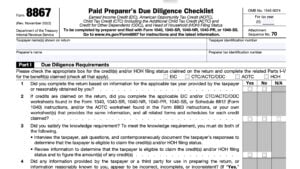

IRS Form 8867 Instructions

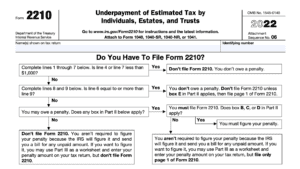

IRS Form 2210 Instructions

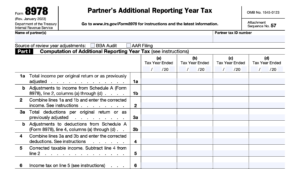

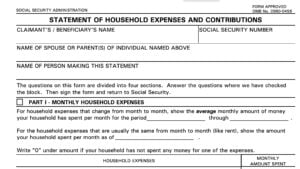

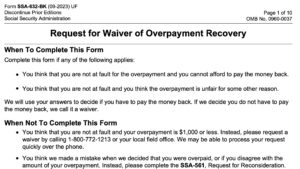

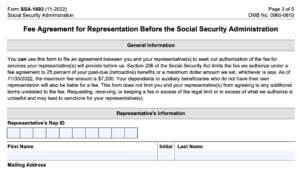

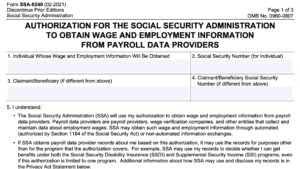

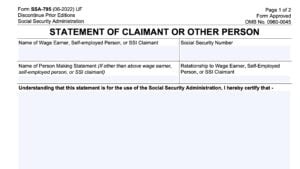

Social Security

Read these in-depth articles to learn more about how to make the most of your Social Security benefits.

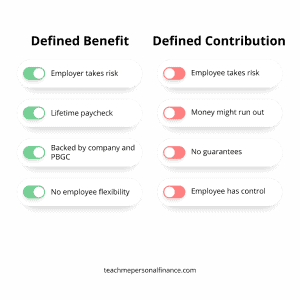

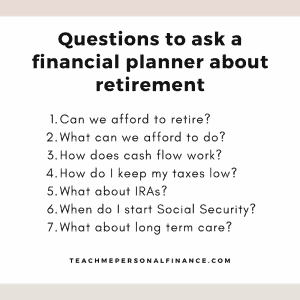

Retirement Planning

Retirement planning is a fundamental part of the financial planning process. Learn about helpful and actionable insight on how to plan your retirement.

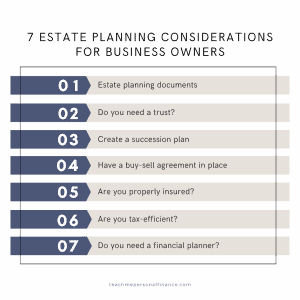

Estate Planning

Retirement planning is a fundamental part of the financial planning process. Learn about helpful and actionable insight on how to plan your retirement.

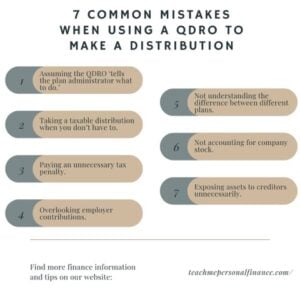

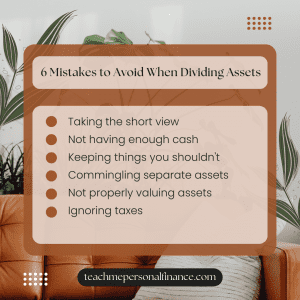

Divorce Planning

Retirement planning is a fundamental part of the financial planning process. Learn about helpful and actionable insight on how to plan your retirement.

Investment Planning

Retirement planning is a fundamental part of the financial planning process. Learn about helpful and actionable insight on how to plan your retirement.